October 19, 2014, marked the 30th anniversary of a fatal plane crash in Northern Alberta, Canada, where a petty criminal emerged as a hero.

27-year-old Paul Archambault was one of four who survived when a small, twin-engine commuter aircraft went down in a snow-covered forest west of the town of Slave Lake.

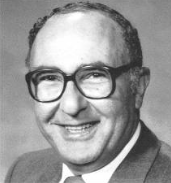

Six didn’t make it, including politician Grant Notley, 45, leader of the fledgling Alberta New Democratic Party.

Paul Archambault, an itinerant labourer and drifter, was being escorted by an RCMP officer to Grande Prairie, Alberta, to face a charge of malicious mischief. Archambault, as they say, was known to police. He’d spent time for crimes that were more serious than mischief — including break-and-enter and theft over $5,000 [car theft] and a high-speed police chase.

Scott Deschamps, the rookie Mountie escorting Archambault from Kamloops, British Columbia, had a hunch he could trust his prisoner, so for the short flight from Edmonton to Grande Prairie, he removed the handcuffs. It turned out to be a life-saving gesture.

Of the four survivors, Archambault was the least injured. The others who pulled through included Deschamps, pilot Erik Vogel and Larry Shaben, Alberta’s Minister of Housing.

I was one of the first reporters to interview Paul Archambault and, it turns out, one of the last. This post is about my dealings with the man over a six-year period.

BOOK ON THE 1984 PLANE CRASH

The definitive story of Paul Archambault and others involved in the plane crash is in a book Into The Abyss by Carol Shaben, Larry Shaben’s daughter.

The award-winning investigative journalist does a superb job of chronicling what happened that fateful night and what happened to the survivors in the years and decades that followed.

Her book is quite the read. One reviewer writes, “… Shaben gives us an astonishing true story of catastrophe and redemption.” More on Carol’s book at the end of this post.

THE CRASH: WHAT HAPPENED

Wapiti Aviation’s Piper Navajo Chieftan clipped a tall tree as the pilot tried to get in under the heavy cloud for a landing in High Prairie. In the darkness, the aircraft smashed into more trees, tearing its wings off. The fuselage flipped and slammed into the ground, ripping open like a sardine can. The plane came to rest upside down.

Archambault and his police escort were sitting at the back of the plane, where the luggage was stowed. Suitcases flew everywhere as the fuselage plowed into the deep snow and frozen earth like a missile, burying Constable Deschamps. The officer was suffocating. Using his bare hands, Archambault dug frantically to get him some air.

After rescuing Deschamps, the prisoner helped everyone make it through the night until rescue workers rappelled from a military helicopter at first light the next morning.

It was one long night.

MY TIME WITH ARCHAMBAULT

I spent some time with Paul Archambault — initially during his first court appearance in Grande Prairie — after that, on the phone … at the inquiry that followed about half a year later … when I visited Grande Prairie … and whenever Paul came to Edmonton.

I liked him. There was something ‘real’ and uncomplicated about the guy; no stick-handling [an ice hockey expression], no circling, no hidden agenda. The more I got to know Paul, he became less of a con and more of a decent human being.

While all this was happening, I worked for CBC Radio News in Edmonton. Just a sidebar here, Harry Nuttall of CBC Television News broke the story of the Notley crash, as it became known.

Within hours of learning of the crash, my employer, the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation [CBC], rented a small plane and flew me, a TV reporter and a cameraman, to Slave Lake.

AIRPORT BECOMES MEDIA CENTER

It was the start of winter and darn cold.

We reporters worked out of the small airport at Slave Lake. When I wasn’t fishing for information, I was on one of the pay phones inside the terminal, filing stories to CBC Radio in Edmonton and CBC National News in Toronto.

Broadcaster Ted Barris hosted a special edition of CBC Radio’s Saturday Morning Show as we tried to keep on top of the breaking story. To get to the area, print and electronic journalists were either packing their bags for flights or heading down the highway, the speed limit be damned.

The Edmonton Journal covered the crash with insightful, on-site reporting by veteran Tom Barrett. The Journal had rented an aircraft and flew over the crash site, snapping birds-eye-view photos that would soon be featured in the newspaper.

I was in the airport terminal and about to file another news update when two teenage girls rushed in through a side door, asking if their mother [Pat Blaskovits] had survived the crash. She hadn’t, but I couldn’t tell them that. We knew that only males had made it out alive. I advised the girls to check with the airport office, to my left, at the end of a hallway. They sprinted in that direction.

Even though the door was closed, I could hear sobbing.

The girls weren’t in the office long. They suddenly bolted past me, sobbing, the older one covering her face with her hand. I watched the pair run to a car in the parking lot. That’s one image I can’t get out of my head.

GRANT NOTLEY

The Senior Editor of CBC Radio News in Edmonton, Cam Ford, made an ‘executive decision’ to go public with the name of one of the passengers killed in the crash: Grant Notley, the Alberta NDP leader.

The move ticked off CBC brass in Toronto. That’s because the Notley family hadn’t been officially notified of Grant’s death — even though his passing was the talk of party insiders, which is how the media first heard about it.

Cam and I discussed this on the phone, wondering if we should go with it. He asked, “What do you think?” reminding me that Grant was a well-known public figure. I said, “Other [news] outlets know about it, so go with the story before we’re scooped.”

The breaking news that Grant Notley was one of those killed in a plane crash prompted the RCMP to set up a roadblock on a northern Alberta highway to intercept a car driven by Grant’s wife, Sandy. “Don’t listen to the radio,” a Mountie told the American-born woman when she rolled down her window.

Sandy knew her husband had been on Wapiti Flight 402, and the plane had gone down … somewhere. She also suspected that not everyone had made it out alive. When the officer asked her not to listen to her radio [CBC], Sandy realized that her husband was in Heaven.

The irony was that Grant Notley had fought for airline service for smaller communities in northwestern Alberta. And here he was, killed in a seat usually occupied by the co-pilot.

Another irony: One year before the crash, Alberta’s Minister of Transportation, Marvin E. Moore, in a letter to Wapiti Airlines, assured that the small airport at High Prairie would be upgraded to instrument approach standards. Instrument approach standards are to flying what headlights are to night-time driving. The promise was not honoured — until after the deadly crash.

If the new equipment had been installed as the Progressive Conservative Government cabinet minister had promised, it’s a safe bet the plane would have touched down at an airport, not in a forest.

I had only met Grant Notley a few times, but he struck me as a decent fellow who cared about others. He hadn’t sold out. He was ‘real.’ Grant wasn’t just a well-known Albertan but an Alberta legend.

For a while, Notley was the sole NDP member in the Alberta Legislature, an army of one.

In late 2014, Grant’s 51-year-old daughter, Rachel Notley, became the leader of the Alberta New Democrats. On May 5th, 2015, she was elected Premier. Her party stunned Canadians by crushing a Progressive Conservative government that had been in power for 44 years.

[Rachel Notley and the NDP Government were “sworn in” on Sunday, 24 May 2015. Click here to see a photo essay of that event, held outdoors at the Alberta Legislature in Edmonton: https://byronchristopher.org/2015/05/24/revolution-alberta-style/]

Soon after the plane crash, I was at the Notley home, on the edge of Fairview. I — along with Tom Barrett and his photographer, Jackie Northam, was there to interview Sandy.

People have asked if Rachel [about 20 at the time] was at home, but I honestly can’t recall if she was or not.

We met Sandy in her husband’s study on the main floor. The room was dimly lit with shelves crammed with books. Here and there, too, were framed photos; one showed Grant standing alongside Frank Dolphin, CBC TV’s legislative reporter.

The woman did her best to look composed, asking the Journal photographer not to snap pictures while she held a cigarette. We asked Sandy how she wanted people to remember her husband. For a moment, she was silent, collecting her thoughts; then she opened up … and teared up. The widow struggled to find the words while I struggled to fight back the tears.

In the kitchen, just around the corner, were friends and neighbours crying and hugging one another. Some had arrived with bags of food, plunking them down on the counter.

I recall feeling very down when I walked out into the dark and the cool air to the white pick-up truck Tom, Jackie and I had rented in Slave Lake earlier in the day.

Shortly after Grant’s death, I went to the Legislature in Edmonton while it was in session. From the press gallery, I spotted Grant’s empty chair in the chamber, his wooden desk crowned with flowers. There was no excitement in the room that day; all the MLAs felt awful. Their greatest critic — “lefty” Notley — was gone; deep down, they knew they’d miss him.

A by-election [special election] was held, and the seat was captured by school-teacher Jim Gurnett of the New Democrats. Hardly a surprise, I realize. A few days later, I was in Gurnett’s office at the Legislature. The man shuffled some papers on his desk as he answered my questions. At one point, he paused, his eyes fixed on a framed picture of Grant Notley on the wall. I turned to see what he was looking at. “Ah, Grant …” I said. Gurnett smiled and remarked, “I suppose I should say something like, ‘Grant is looking down, and he’s smiling’ … but that would be too corny.”

A final Grant Notley story: I once covered one of his speeches — forget now what the event was, except that it was somewhere in Edmonton — where Grant made a side remark which spoke of something that had bothered him. It was this: He said people came to the NDP with their problems but not their votes. And so I did a story on it.

Seeing how Alberta’s political landscape has dramatically changed, I’m reminded of Grant’s words that day.

A poignant photo: Grant Notley Park in Edmonton; 6 May 2015, the day after the Provincial Election. The newspaper headline tells it all. Click to enlarge. [Photo by former NDP MLA Jim Gurnett]

Sandy Notley remarried [Alan Kreutzer]. The woman — who made a name for herself by devoting many hours to foreign development — died from cancer in 1998 at 59. She is buried in Fairview.

FIRST MEETING WITH THE PRISONER

For days, the deadly plane crash was the lead news story in Canada. The attention shifted from six dead … to one survivor in particular — the man sporting a blue jean jacket and handcuffs — especially after Larry Shaben labeled him a hero. We had his name — Paul Archambault — but no interview. Who was this guy?

My first chat with the prisoner came just minutes before his court appearance in Grande Prairie, a few days after the crash.

About an hour before Archambault stood before a judge, I dropped around to the RCMP Detachment nearby, where a senior Mountie revealed he’d recommended to the Crown — given what Archambault did to save his officer’s life — that charges against the prisoner be dropped. He also asked that I not do a story on it until it was “official.” I said, fine with me. We shook on it.

I then walked into the courtroom. To my left sat a group of reporters on a bench — like birds on a wire. I sat on the right. I was alone. But not for long. A young, anxious man with shoulder-length hair and a jean jacket plunked himself down beside me, to my left. I took one look at him and knew instantly who he was. I said, “You’re Archambault, aren’t you?” He looked my way and in a near whisper said, “Yes. Who are you?” I told him my name and where I worked. We shook hands, and I gave him my business card.

I asked Archambault to call collect whenever he could. Over the years, he did just that.

We had only minutes to chat before things got rolling in court, so I fired off some questions. I wanted to know if he was considering a lawsuit because of the crash. Archambault’s response said a lot about him. “No,” he replied, “I just want my blue jeans back.”

I whispered that charges against him would likely be thrown out. He smiled.

The charges were indeed dropped. Mr. Archambault was now a free man.

A group of reporters, myself included, gathered around Archambault outside the Courthouse and did a formal interview. I can’t remember everything that was said, but for some reason, I vividly recall that local reporters let the out-of-towners [the “Big City” reporters, if you will] ask the first questions. Perhaps it was more a case of intimidation than politeness, not sure.

Archambault later revealed he was off to British Columbia to attend some sort of self-improvement course paid for by his uncle Denis, a criminal defense lawyer in Prince George, B.C. I briefly spoke with Denis on the phone; he struck me as a thoughtful man.

From time to time, Paul phoned with updates on how well he was doing, or not doing.

He again settled in Grande Prairie, working at a small family restaurant downtown. His girlfriend, Sue Wink, waitressed at the same restaurant.

PAUL’S MEMORIES OF THE CRASH

The accident haunted Paul; I could tell because he didn’t talk about it until I raised the subject.

I wanted to know what happened that night, how he and the others made it through the ordeal, their fears, gains, setbacks, what they talked about over a fire, all that stuff.

Once Paul got talking, he didn’t shut up. He described burning branches and twigs and luggage to keep warm … and that the policeman — in severe pain from numerous broken ribs — complained it was either too hot or too cold. The prisoner kept moving the officer to keep him content. Paul said he kiddingly nicknamed the cop “whiner.” Larry Shaben — nearly blind because his glasses had been shattered in the crash — got tagged “Mr. Magoo,” after the poor-sighted TV cartoon character.

They were four unlikely characters trying to survive in the middle of nowhere.

From the pilot, Paul said he got instructions on where the emergency locator transmitter was located [at the back of the aircraft]. Throughout the night, the prisoner kept turning the beacon off and on. Circling overhead, rescue planes picked up the intermittent signal. They knew that at least one person had survived the crash.

The more Paul talked about his night in the bush, the horror stories slipped out, like whispered secrets in a bar. In the darkness, he repeatedly returned to the fuselage to comfort a passenger still trapped in the wreckage. The man was hanging upside down. Paul said he could not pry him free because he was wedged in too tight, so he gave him words of encouragement. Unable to speak, the badly injured passenger simply responded by moaning.

Paul said it bothered him to hear the man in pain and banging on the plane with his arm. At some point in the night, all was quiet in the fuselage and the number of dead rose from five to six.

The prisoner recounted that some time after the man died, he returned to the aircraft, while it was still dark, to have a look at the man he’d been comforting. He flicked on his lighter, half expecting an explosion … but there was none. But what Paul saw so frightened him that he immediately shut off his lighter and left. The man, he said, had no face.

According to Paul, another victim appeared to be peacefully sleeping in his seat, still belted in, with no apparent injuries, save for a trickle of blood on a small ball of ice that had formed on his lips.

Sitting around the campfire, Shaben turned to Paul and said that some “important people” had been on the plane. Before the crash, Paul hadn’t heard of Grant Notley — nor Larry Shaben. Paul once told me, “Larry’s some kind of big wheel in the Government.” He was, in fact, a provincial cabinet minister.

Shaben asked what others would wish for if they could have anything they wanted. The cop said he wanted to be with his wife, Shaben wanted a hot bath and the prisoner a joint.

Rescue came at daylight when men with the Canadian Air Force rappelled from a helicopter.

Years after the accident, Paul shared that he wanted to return to the crash site and spend a night there. He asked if I’d go with him. I said sure, but it never happened; life and other stories got in the way. I now regret that, getting out there with Paul with a tape recorder, etc. …

THE HEARING

I again ran into Paul in early 1985 at a government [Canadian Aviation Safety Board] inquiry in Grande Prairie into Wapiti Flight 402. Next to pilot Erik Vogel, Paul was one of the key witnesses.

The hearing was held in a hotel on the western edge of town.

It was during a break in the proceedings when a reporter — freelancing for an aviation magazine — came up with the idea to photograph all four survivors. Cameras flashed away.

MEMORABLE MOMENTS WITH PAUL

I’d booked a room at the same hotel. One evening there was a knock at my door; I opened it to see Paul and Sue Wink standing there, with Paul in an upbeat mood, bopping from side to side. I invited them in. Paul bounced up and down on my waterbed like a kid on a trampoline, with him suggesting something to Sue [use your imagination what that was about]. The voices and giggling made it difficult to record my news reports. I had to ask for quiet.

After the reports were filed, we drove into town where Paul proudly showed me his carpentry work in the basement of the restaurant where he worked. He’d built some wooden stairs. The workmanship wasn’t professional but when Paul asked me about it, I said it was good … and they were lucky to have a worker like him. He grinned from ear to ear.

Paul liked the restaurant owners because they trusted him, pointing out that one night they let him deposit the day’s receipts in the bank.

Paul Archambault reminded me of the 1960s country song Branded Man by Merle Haggard where a former prisoner is haunted by his past.

Sue offered this interesting insight: Paul had become a bit of a ‘celebrity’ in Grande Prairie, but those now wanting to hang out with him were the same people who had shunned him before the accident.

Paul, meanwhile, didn’t seem to know what to make of all the attention. He kept saying, “I’m no hero.”

The more I got to know Paul, the more he talked about things that were important to him: his youth and run-ins with the law, including the time he stole a car back East.

Paul walked with a distinct limp. We were chucking a frisbee in a park in Grande Prairie and I noticed he couldn’t run very well. “What’s wrong with you?” I asked. He then told me about the time he had crashed a stolen car in a high-speed police chase, leaving him with a permanent leg injury.

NOT MEASURING UP

In a telephone interview from Aylmer, Quebec, near Ottawa, Paul’s mother, Gayle Archambault, shared that Paul could never “measure up” to his father — a great athlete, she said — and it really bothered him. She said Paul consistently tried to be accepted by his father but whatever he did was never good enough. I was reminded of the adage that it’s easier to raise a child than to repair an adult.

When the inquiry wrapped up, the St. John Ambulance presented Paul with a framed certificate for helping people on the night of the crash. Paul tucked the award under his arm and walked out of the second-floor conference room towards an open area, near some large windows. From a distance, I watched as the former prisoner studied the certificate, as though it was written in a language he couldn’t understand.

I then approached with what I thought was an easy question with an obvious answer. “You’re going to put this up on your wall, right?” Paul turned and said, “No, I’m going to mail it to my father. Maybe now he’ll be proud of me …”

Years later when I relayed that conversation to Paul’s mother she gasped, “Oh no …” and began to cry.

FRONT PAGE CHALLENGE … AND A SECRETARY

In May 1985, Paul Archambault was a guest on CBC’s Front Page Challenge, a TV series that ran from 1957 to 1966 where journalists tried to guess the news story associated with a mystery guest.

The thing that most impressed Paul was that Mother Corp got him a rental car and put him up in a nice hotel. The drifter and petty criminal was treated like a real human being. Paul beamed when relaying the story.

I sensed Paul wasn’t after glory or fame, just acceptance.

That’s the same impression ‘Sharon’ had of Paul. Shortly after the plane crash, the secretary and Archambault — whom she didn’t know — were on an Air Canada flight from Toronto to Edmonton. “He happened to be sitting behind me with a very annoying neighbour,” Sharon recalls. “He was so patient and never said a word.”

After the flight attendant apologized to Archambault, Sharon asked him to join her for a few hours. “We ended up having a couple of drinks and him telling me his story. He was very open and showed me a small article in the Edmonton Sun that announced his release.”

“I was very happy to meet him,” Sharon says, more than a quarter of a century later, “because I had read the articles when the incident first occurred and had wondered about this ‘prisoner’ who had saved those people on the flight.”

“I really enjoyed our conversation and will remember him as a very kind-hearted person. I wished that he would have had a good life. I am sorry to hear that he did not make it past 33. RIP, Paul.”

DINNER OUT IN EDMONTON

Paul phoned when he got to Edmonton — though usually without much warning — [“hey, I’m at the bus station … wanna hook up?”]

We had several meals together. I once bought him dinner at a family restaurant on Stony Plain Road, just west of 156th Street. Paul Archambault was the first prisoner I really got to know and he forever changed the way I saw criminals. I saw some good in him, a man longing to prove his worth, if you will.

Perhaps he was simply trying to find himself, but who isn’t? And aren’t we all seeking approval from our parents?

When I drive by that restaurant I think of Paul, the way he sat at the table, nervously straightening his cutlery, looking up. He felt uncomfortable but I could tell he enjoyed the contact. For me, Paul didn’t have to measure up; he’d already done that one freezing night in a Northern Alberta forest with four lives on the line.

Another time I had him out to our house in Spruce Grove, just west of Edmonton, where my wife Hardis made him a meal. The kids liked him.

According to a 27 May 1991 Matthew Ingram story in Alberta Report, Paul Archambault moved back East after the crash but couldn’t stay out of trouble. He returned to Grande Prairie where he worked for Diamond Caterers. His boss, Bill Taschuk, was quoted as saying, “He seemed to be kind of a loner. He’d do his job, collect his pay and off he’d go.” Taschuk never knew that his employee was the hero of the Notley plane crash.

If there’s a moral to this story, it’s that there’s greatness in all of us.

Paul swore now and then, but it didn’t bother me because I swore too. After all, I worked in a newsroom where it happened all the time.

Paul wasn’t sophisticated or moneyed-up, but neither was he like some Alberta politicians who voted in favour of retroactive legislation to put the screws to some poor Natives fighting a “land claim” with a government that held all the cards. In other words, Paul wasn’t a whore for the status quo … and unlike some journalists, he didn’t show up for work holding a jar of vaseline.

DEAD AT 33

Paul Archambault was last seen on a bitterly cold night, November 8, 1990, leaving the Salvation Army hostel in Grande Prairie. Next spring, when the snow melted, railway workers came across his body in a watery ditch.

Police believe the prisoner-turned-hero froze to death, his body covered by drifting snow. The man who had been the center of so much media attention died alone, his remains unnoticed for half a year. His family wasn’t particularly worried he might be missing since Paul sometimes didn’t check in with them for months.

I called Gayle Archambault soon after her son’s body was discovered. After she stopped crying she revealed she had few of her son’s possessions, that the RCMP hadn’t sent anything Paul had on him when his body was found. I put in a call to Constable Ian Sanderson at the Grande Prairie Detachment. The officer said, “well, we have his wallet …” I said something like, “Well, here’s his mother’s address …” Sanderson mailed Paul’s wallet to his mother. Gayle phoned all excited the day it arrived.

A year or so later, I bumped into Sanderson at the Courthouse in Edmonton. By this time he had been promoted and transferred to the RCMP detachment in Fort McMurray, Alberta. Sanderson was as I had imagined him to be: distinguished and someone who looked you straight in the eye, a peace officer the public would respect.

Larry Shaben died from cancer in 2008. Paul Archambault’s parents are also deceased.

The last time I spoke with Gayle was in the spring of 1993. She said her son’s grave was in a “nice spot.” That nice spot is Notre Dame Cemetery, a Catholic graveyard, on Montreal Road in Ottawa. Paul was buried on 27 May 1991; officially his date of death is listed as 8 May 1991.

Both Gayle and her son, Paul Richard Archambault, are buried side by side in Section 64-D, plot 1759.

[Image courtesy of Google]

INTO THE ABYSS

You can find out more about Carol Shaben’s book, Into The Abyss [‘How A Deadly Plane Crash Changed The Lives Of A Pilot, A Politician, A Criminal And A Cop’] by going to this site: www.carolshaben.com

Into The Abyss is published by Random House of Canada. Various bookstores are selling it for $29.95; Costco for $17.89. The ebook version is $15.99. Prices are in Canadian dollars.

BBC Radio 4, in its coverage of Into The Abyss — its “Book of the Week” — featured a photo from another province — British Columbia [Mt. Robson in the Canadian Rockies] — more than 500 kilometers from the crash site. Close enough I guess.

Note: the black and white photo of Paul Archambault is courtesy of Alberta Report.

The book was later released in the United States by Grand Central Publishing. The cover was changed to include peaks of the Rocky Mountains, hundreds of miles away.

Here is the cover of Into the Abyss by Pan Macmillan UK …

![Grant Motley [photo courtesy of Record Gazette]](https://byronchristopher.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/10/grant-notley.png?w=253)

Nice story Byron, thanks for sharing it.

LikeLike

Masterful writing. You cover all the details with compelling style that pushes me paragraph to baited paragraph.

LikeLike

Interesting story. It reminded me of something my mother always says … “There’s good in the worst of us and bad in the best of us.” Archambault really never had a chance. So many criminals (so called) are the result of abuse and neglect. Loved the quote on raising the child being easier than repairing an adult. So very true.

LikeLike

I knew Grant Notley as I was on the Alberta New Democrats Executive. He was literally taken before he was able to see the gains the party made after his death. Paul Archambault, as you well documented, was also a hero helping to save others on that fateful flight. It is indeed sad that he was not able to savour his role over the years.

LikeLike

Thanks for posting this Byron, it’s an incredible story.

LikeLike

You took the time to show him some acceptance in spite of his shortcomings.

LikeLike

This blog brought back so many good memories of Paul. Thank you. I remember when I found out he had died; for years afterwards I swear I saw him in various places. He was good, and we loved him. He will never be forgotten and lives on in our memory.

LikeLike

Carol Shaben was obviously protecting the family by never revealing the passenger’s name that lived for several hours after the crash.

LikeLike

The man was right, he was not a hero, he did what all of us should do in that situation. However, after the event you discovered a real human being. I’d trust a guy like that over many big business men or corporate slimeballs. Great story.

LikeLike

I worked in Mr. Shaben’s office during and after the accident. Paul would call him from time to time. It was a call that Mr. Shaben always wanted to be interrupted to take. They would chat for a while with Paul telling him what he was doing and Mr. Shaben offering encouragement. I just heard Carol on the radio discussing this and am looking forward to reading her book.

LikeLike

Until yesterday I knew nothing about Paul Archambault or the plane crash so many years ago, but it was a very touching story to hear on the radio. This prompted me to come home and search Paul on the Internet. I came across your article ‘A Hero Named Paul.’

When I read his story and heard his story I felt … what a shame for this man to be forgotten, so I copied his picture and saved it and told myself that on occasion I will look at it and remember this man for his courage, and what he came through and helped others come through.

It was sad to hear about his death at such a young age, and to hear that he was trying to impress his father and that there was a lack of father-son relationship.

Paul was deserving of more than a certificate. He should have received a medal — the Canadian Medal of Bravery.

I will think of Paul for many years to come and will say a prayer for him.

LikeLike

I’ve encountered a number of people who’ve served time. Generally speaking I find them a better class of people than Canadian government lawyers, bureaucrats and politicians. Smarter, more interesting, more decent, more trustworthy and more principled.

LikeLike

I am Paul’s little sister … Nadia Archambault. After our father divorced (Paul’s mother), he married my mother and I was born shortly after. Paul died when I was 12 — and although he lived a hard life and had his run-ins with the law, I remember him as a soft and gentle person. My last memory of Paul is him helping me colour Tweety Bird with yellow crayon, trying to get me to stay in the lines.

You have no idea how much it means to me that complete strangers are thinking of him, and remembering him … my heart breaks that he died such a lonely death.

Thank you all for caring.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Nadia, this was such a nice story about your brother Paul. I use to hang out with your other brother Daniel (Archie) when we were young back in Aylmer, Quebec.

I also knew your sister Angele quite well; I married her best friend Sue Albert back in 1983 … and are still marrried. I don’t know if you remember her.

Well, hope things are good with you and your brother and sister.

LikeLike

I have just finshed reading Carol Shaben’s book. Thanks to her, many people will read about Paul Archambault, and he will be forever remembered as the genuine kind person he was.

The book was so uplifting a story until I came to the tragic part of Mr. Archembault’s death. I had so hoped to finish the story reading of him having made peace with himself and living a contented life. How unrealistic of me, those damaged as children never recover good self esteem to be truly happy. Every day is a challenge to fight depression and insecurity.

Nadia, I think your brother was just tired, and is now resting in peace. Thanks to Ms. Shaben’s book, may he always be remembered in our prayers.

LikeLike

I had to look up Paul after reading the story of the crash in the Reader’s Digest, sad he died so young … and the way he died. Thanks for the story.

LikeLike

I just read the story in Reader’s Digest; was lucky enough to come across your follow-up. Thank you so much for that. What a sad end!

As my old Daddy used to say, “there’s some good in everyone.”

LikeLike

Wouldn’t have enjoyed the book so much if Paul wasn’t in it. R.I.P.

LikeLike

Thank you for your recollections Byron.

LikeLike

Thank you for seeing the good in Paul. Not everyone does the right thing in such a situation — he was a hero, and it’s wonderful to hear his friends and family describe the honest and genuine person he was. What a legacy.

Byron, you’ve elevated the field of journalism by finding the heart of this story in Paul. I will remember to look for the good in people, too.

LikeLike

War and disaster often provide scenarios wherein those who are useless in normal times can shine. Often those labelled ‘useless’ have had very bad luck with respect to opportunities, and often a few bad incidents instil poor coping/habits that prevent good opportunities in the future. Society has very few channels for folks to reload and try again, especially once they have been processed by the criminal justice system. Such is life.

Prisons are extensions of the systemic problems of society as much as they are repositories of personal failures — to the extent that they are the latter, they should imprison for life. However, where the failures of individuals stem from external sources/mistakes, there should be a reload/relaunch function available.

I hold two very disparate views on the subject. I think all white collar crimes should qualify for life imprisonment (preferably solitary tip death), since white collar crimes are premeditated. The deterrence of such stiff penalties would likely have a salutary effect, as opposed to blue collar crimes where there is very little deterrence.

I am lucky that none of my network/family are ex-cons (or prison guards), but I do feel that wasting human potential is a crime in itself. Societies that get the most out of the human capital available to them should be winners in the long run.

We should revamp education and prisons/justice to be the best for society, which would be a backhanded victory for the individual.

LikeLike

I am just reading Carol Shaben’s book; Into the Abyss. I am enjoying it very much.

I remember this happening in 1984 (I lived near Grande Prairie at the time and was familiar with who Grant Notley was) but of course not all the details that I am discovering in the book. It was a terribly sad story when it happened and on occasion have thought about it over the years.

The young man, Paul, was truly a hero and is unfortunate he lost his life so young. He was a good person.

LikeLike

Nice story.

LikeLike

After reading a number of “Bush Pilot” books recently out lining the horrific efforts these pilots go through each and every day they suit up, it was suggested I read “Into the Abyss.”

Having worked as a “Peace Officer” with Corrections, I can relate to the troubles Paul experienced over the years both inside and outside of jail.

The story was a great one in detailing the events of all 4 men who survived the crash only to be haunted for the rest of their lives in one way or the other.

They are all heros, in my opinion.

LikeLike

Funny, I was in the process of writing a blog post about the plane crash and its aftermath when I stumbled on your well-written account, Byron. It was an experience I will never forget.

By the way, the Journal photographer with me, Jackie Northam, later was in Rwanda working for PBS and witnessed and reported on the Hutu massacre of Tutsis.

I enjoyed getting to know you on that assignment and appreciated the time you introduced me to David Milgaard. Thanks for the nice words, my friend.

LikeLike

I stumbled across this story (and Carol’s book) while searching for an earthquake crack called the Abyss and wondered what happened to Paul. Thank you.

LikeLike

Hi Cris, Paul Archambault died in 1990. It was bitterly cold when he left the Salvation Army Hostel in Grande Prairie, Alberta in November that year. His body was discovered in a ditch next spring. There’s more in the blog story … see Chapter ‘Dead at 33.’ Thanks for writing.

LikeLike

I knew Paul for a few short weeks when we worked for a carpet company in Kirkland, Montreal. He told me the real story what happened when the plane crashed.

One thing I remember of him was his horrible language which got him fired.

He told me when the plane crashed and he came to his senses, the first thing he did was to dig out the officer and take his gun. He was going to shoot him in the head but decided to look around first and realized he had no where to go.

He was brought up with his father beating him most the time.

I was the only one that got along with him at work. I would never introduce him to my family, but I did see good in him.

PS … just giving you a little bit of truth.

LikeLike

I’m sorry, but that is a LIE.

I am his little sister — and Paul was NOT a violent person. He would have NEVER killed anyone, especially a police officer. Shame on you for saying this when he is not alive to defend himself!

LikeLike