Dorvil and Lottie Ramsay. Image courtesy of the Ramsay Family.

For nearly a century, two rock-painted crosses on an extinct volcano in Campbellton, New Brunswick have been a grim reminder that life can vanish in the blink of an eye …

On a frosty evening in November 1924, two local sisters — Dorvil [Ramsay] McLean and Lottie Ramsay — hiked to the top of 1,000-foot Sugarloaf Mountain.

To descend, the girls chose the most dangerous route — the North Face. They paid the ultimate price, plunging to their deaths.

Dorvil [left] was 22; Lottie [right] was even younger.

Your choice: silence … or a gentle piano number, “Broken Hearts” by Michael Ortega. The piece runs for five and a half minutes. [You can find it on iTunes.]

Sunday, November 9, 1924

It was around four in the afternoon when Dorvil and Lottie set off to climb one of Maritime’s best-known clumps of rock, Sugarloaf Mountain. They followed a trail that snakes up the eastern spine of the mountain, the same one hikers use today.

There’d been a light rain, and rocks on the path were slippery, making it easy for someone to lose their footing. One cautious step at a time, the girls slowly made their way up the mountain …

Darkness was fast approaching when Dorvil and Lottie stood on Sugarloaf’s highest point, a popular destination even then. It was also a tad chilly, but the view — wow!! — postcard-beautiful! As always. The first humans to stand at that spot would have been First Nations People — the Mi’kmaq — and that would have been hundreds, perhaps thousands of years ago.

It’s likely a three-masted sailing ship, perhaps two, bobbed gently in the harbour that fateful day. The big wooden ships wouldn’t be in town long; winter’s bite was already in the air. The mighty Restigouche River would soon be a blanket of snow and ice — ice so thick that horse-pulled wagons carrying heavy loads could safely cross.

When the sun dipped beneath the horizon in the Matapedia Valley, out came the twinkling lights of the Town of Campbellton and surrounding villages.

We’ll never know what possessed the Ramsay sisters to make their way down the face of the mountain, a high-risk venture at the best of times. But at that hour, with darkness descending?? Wow. Risky, for sure.

We could analyze this for eternity, but the bottom line is that no one can confidently say what the girls were thinking that day. At the time, many questions went unanswered. 100 years later, there are still no answers — only theories and everyone in town seems to have one. It all boils down to this: key information will always be missing. Too much time has passed.

No one saw the girls fall. The piercing screams must have been heard for miles, but nobody heard them. That’s because the area wasn’t developed like it is today. Back in 1924, there was no groomed hiking trail circling the mountain base, just wilderness.

FAMILIES & THE SEARCH

Dorvil [Ramsay] McLean, married for less than two years, had a seven-month-old boy at home. Little did the young mom know she’d never see her child again. If you believe in Heaven and a Life Beyond, 1945 would see a mother and child reunion. More on that coming up.

When Dorvil and Lottie failed to show up for supper, their parents, Jane and Sydney, knew that something was amiss. It was so unlike the girls not to let the family know where they were.

Jane was a stay-at-home mom, which was not unusual back then. Sydney was a railway fireman who earned his paycheque the hard way by shovelling coal on the old steam locomotives.

The girls came from a large family. Besides Mom and Dad, there were six siblings [two sisters and four brothers].

It didn’t take long for panic to set in at the Ramsay household at 15 Hillside Street, on the north end of town, down by the train tracks. Mom and Dad had no idea where their girls were, and it gave them fits. They talked to relatives and neighbours, but no one had seen them. That was not a good sign.

A younger brother was given a few cents and told to leave the house for a spell while the adults tried to make sense of things.

When Dorvil and Lottie failed to return home, it was obvious something had gone terribly wrong. At this point, the emotional strain must have been unbearable. We can only imagine.

Around 10 PM, a group of men armed with flashlights and high hopes searched for the girls. No luck. Where could Dorvil and Lottie be??

Dreading that proverbial knock on the door, Mom and Dad nervously paced the floor. Turns out, their prayers — uttered non-stop — were for naught. The girls were already in Heaven.

No one slept well that night. There was absolutely no sign of Dorvil and Lottie. When the sun came up, a small search party set off to find them. Several men reached the top of the mountain where they picked up some tracks in a thin layer of snow. The trail led towards the face. Oh no!

Following a set of footprints, searchers gingerly made their way down the front of the mountain …

Dorvil and Lottie’s trail zigzagged here and there as though they didn’t know where they were going. About halfway down the mountain, hearts sank when the trail ended at the edge of a steep cliff with a drop of more than one hundred feet. No one could survive a fall from that height.

The men cautiously peered over the side and called out. No response. And so they called out again and again. The silence signalled they were no longer on a rescue mission.

Three more members of the search team — policeman William Smith and two civilians, Mr. J.H. Moores and Mr. Gay, located the girls’ cold, lifeless bodies at the base of the cliff.

According to a 1924 story in the local paper, The Graphic, Dorvil was the first victim found; her body was located among the rocks. Lottie’s body was a short distance away, hung up on a tree.

The bodies were wrapped in blankets and carried down the mountain.

A grim-faced policeman then went to the Ramsay house and gently tapped on the door. He had some heartbreaking news no parent should ever hear.

The girls’ remains were taken to Graham’s ‘undertaking rooms’ in Campbellton.There was no autopsy. “No need,” according to coroner Doctor Martin who promptly concluded the girls died from severe head injuries.

The funeral, held mid-afternoon, was one of the largest Campbellton had seen. Here’s a portion of a write-up in the Graphic: “A large number of autos, [horse] carriages and people on foot followed the funeral cortège to the rural cemetery. Floral tributes were many and beautiful, showing the esteem in which the two young ladies were held …”

Dorvil and Lottie Ramsay’s tombstone can be found in the sprawling Rural Cemetery in the West end.

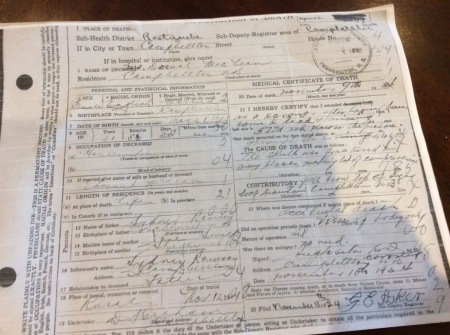

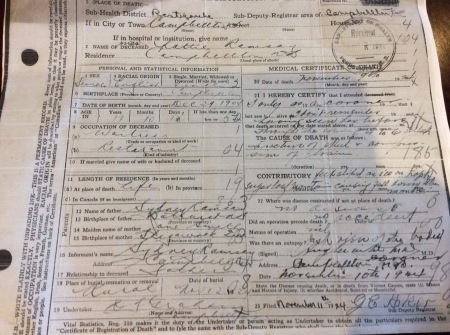

DEATH CERTIFICATES

Little is known about Dorvil and Lottie because the accident happened so long ago. But there’s another reason. Family members — especially the parents — just didn’t want to talk about it. So deep was their pain.

Official death certificates state “accidental death.” The historic documents shed more light on the girls and how they died …

Arabella Dorvil [Ramsay], born in Campbellton in 1902, had recently married Edmund McLean. On the official statement of cause, date, and place of death. Her occupation was listed as a housewife.

Cause of Death: “The skull was fractured in many places, making [a] lot of compressions.” Translation: massive head injury.

Contributory: “Fall from top of Sugarloaf Mountain in Campbellton, NB.”

Lottie Sarah Ramsay’s death certificate lists her occupation as a restaurant waitress. Lottie, who was also born in Campbellton, was single.

Incredibly, Lottie had three different birthdates. Her death certificate [see below] indicates 1904. But according to her birth certificate, she began her first trip around the sun in 1906. Lottie’s tombstone [see photo above] indicates she was born in 1905. Take your pick.

Back then, vital stats [including the correct spelling of names] apparently weren’t a big deal.

“I don’t remember having seen her before,” writes the physician who completed Lottie’s death certificate, “… I only [saw her] as a coroner.”

Under ‘Contributory,’ Doctor Martin noted: “Feet slipped on ice on top of Sugarloaf Mountain causing fall down the mountain …” It’s interesting the good doctor came to that conclusion. Could it be that someone — perhaps the coroner or a police officer — spoke with searchers who followed the girls’ tracks to the cliff’s edge? As part of an investigation, members of the search party were likely interviewed to help determine if the deaths were an accident or the result of foul play. That’s standard procedure nowadays, and I suspect things were no different in the 1920s.

Rumours of the girls being “chased by a bear” … hmmm … perhaps not. When the accident happened, bears had already been hibernating for at least a month. And if a bear was not in its den that particular evening — for whatever reason — the bruin would’ve been scrounging for food and water, and there wasn’t much of that at the top of the Sugarloaf.

Also … no one reported seeing bear tracks.

Here’s something else to consider: going down a mountain is sometimes more dangerous than going up a mountain, especially the Sugarloaf. The Sugarloaf has trees and bushes … and in spots, the descent seems no different than a rough hike in a forest. What’s deadly deceptive is that because shrubs and tree branches hide one’s view; one moment you’re on solid ground, safe as can be; the next moment, you’re walking on thin air and down you go.

I know that firsthand. Although I’m afraid of heights, I carefully followed the girls’ route to the point where they fell. Sure enough, if one isn’t mindful of every step … they’re in big trouble. There’s no ledge to help break one’s fall. When the Ramsay girls tumbled off the cliff, they were doomed.

Given the lateness of the day, perhaps this is what happened to the lead girl … and when her sister reached to grab her, their fate was sealed.

Some have speculated the girls may have been alive for a while after they hit bottom. Given the severity of their injuries, that probably didn’t happen. Due to the long drop, Dorvil and Lottie were likely unconscious within seconds and dead within minutes.

The distraught parents, Jane and Sydney, were forever in mourning. The unexpected deaths of their children hit them hard. Ditto for 24-year-old Edmund, who lost his wife and now had an infant at home to care for [relatives would help out]. Many in the small, tightly-knit community — where everyone seemed to know each other — were shocked and saddened.

One can only imagine the number of prayers whispered for the two girls. Then and now.

And so, a young waitress and a stay-at-home mom became two of Campbellton’s best-known citizens — not because of who they were, but how they died.

The Ramsay girls will never be forgotten. 300 years from now, Campbelltonians will still be talking about them — more so than any politician, soldier, doctor, sports hero, ship-maker, you name it.

PAINTER ALEX JOHNSON

Alex Johnson went beyond making devotions for the girls. On May 28th, 1925, half a year after the accident, the former World War One sniper aimed at creating a memorial that would be around for years.

With the help of his older brother, Seely, the 26-year-old made his way up the face of the mountain, carrying gallons of white paint. He pulled out a brush and began painting two rock surfaces. It was a full day’s work.

Would Alex have gotten permission from the owner of the mountain? I suspect not. Times were different.

The next morning, people in Campbellton woke to find a pair of crosses on the Sugarloaf. There wasn’t a soul in town who didn’t know what the crosses represented.

Alex Johnson made the climb time and time again to repaint the crosses. Here he is, in May 1955, at the foot of the main cross. Note the tiny cross stitched to his jacket. Click to enlarge. [photo supplied by John Van Horne]

Alex Johnson provided some form of closure — not only for himself but for everyone in the community.

It was essentially a labour of love. Alex continued to paint the crosses on his own time — and without compensation. That’s how things got done back in the day.

Angie Johnson recalls her father discussing the “great sadness” in town. Alex wanted to do something special so the girls would never be forgotten. The result was a one-of-a-kind memorial that could be seen for miles.

In an ironic twist, the photo of the Ramsay sisters [top of the story] shows both wearing tiny crosses.

With the help of a sturdy leather harness, Alex Johnson painted the large crosses without getting injured or becoming a fatality himself.

This is the leather harness used by Alex Johnson to paint the crosses. Click to enlarge. [Photo by Author]

When Irene Doiron was a kid, she enjoyed climbing the Sugarloaf with friends. Irene’s mother worried she’d get hurt. To discourage her from doing that, she showed her daughter newspaper stories of the accident.

Alex Johnson, a founding member of the Royal Canadian Legion in Campbellton, died in 1997. He was 98.

[Photo credit: Angie Johnson and John Van Horne]

The man who initially painted the crosses on Sugarloaf Mountain is buried in the same cemetery as Dorvil and Lottie Ramsay.

RAMSAY FAMILY REACTION

The large crosses didn’t go over well with the Ramsay family, especially the mother. That’s understandable. Seeing the crosses day in and day out was a painful reminder for Jane that her two girls were never coming home.

DORVIL’S ONLY CHILD

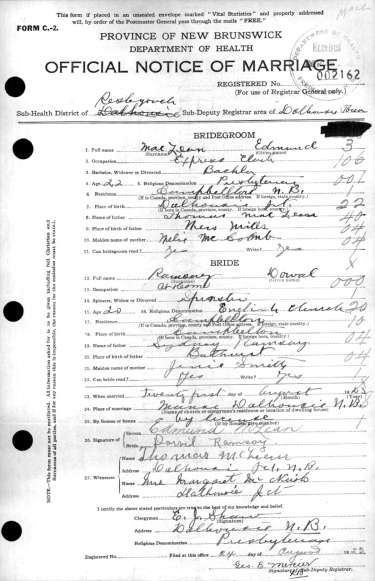

Dorvil married when she was 20. Her husband, Edmund, was 22. The young couple took their vows on August 21st, 1923.

They hadn’t been married 15-months, then Dorvil was gone.

The ‘Official Notice of Marriage’ for Edmund McLean and Dorvil Ramsay. Edmund is listed as a ‘bachelor,’ Dorvil as a ‘spinster.’ “Can the bridegroom read? Yes. Write? Yes.” Can the bride read? Yes. Write? Yes.” Click to enlarge. [Source: Ramsay Family.]

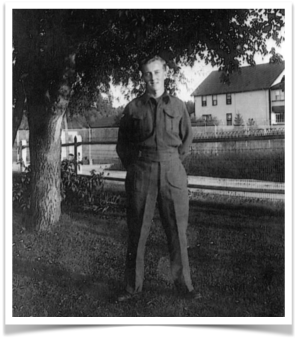

Before Sterling could finish high school [like so many teens in the day], he eagerly signed up at a military recruiting office in Fredericton, New Brunswick, where he was given an army uniform. After the 120-pound lad completed basic training, he was on a ship crossing the Atlantic Ocean for more training in England … then to see action in the ‘European Theatre’ of World War Two.

Trooper Sterling McLean [Reg # G3906] was a member of the 28th Armoured Regiment [tanks], based in British Columbia.

And like so many teens and young men back then, Sterling never returned home.

[Courtesy of Library and Archives Canada.]

[Canadian Troops in Friesoythe. Photo taken on April 14th, 1945.]

Like his mother, Sterling died young; he’d just turned 21.

Trooper McLean is one of 1,382 soldiers interred in a Canadian War Cemetery in Holten, Netherlands, about two hours’ drive from where he was killed.

August 1943. Before going overseas, Sterling McLean visited his father in Low, Quebec [north of Ottawa]. He trained in England and took part in the D-Day Invasion and the liberation of Holland. [Photographer unknown]

This is what an email looked like in 1945. Millions of telegrams were delivered worldwide during wartime, bearing terrible news. Click to enlarge. [Image courtesy of Library and Archives Canada.]

On the white tombstones in Holten are touching tributes: “Far from home he died that we might enjoy life” … “Memories are treasures no one can steal; Death leaves a heartache no one can heal” … “He is not dead, he is just asleep” and … “Far from those who loved him but in eternal peace with God …”

On the tombstone of Edmund and Dorvil’s son, there is no personalized tribute — only a cross.

Left: Sterling [circa 1934, 10 years old?] and Sterling [14?] with his dad, Edmund, in Low, Quebec [circa 1938]. Edmund left Campbellton in the early 1930s, settled down in Low and remarried. He died in the 1970s. Photos courtesy of Penny Warne.

ON THE HOMEFRONT

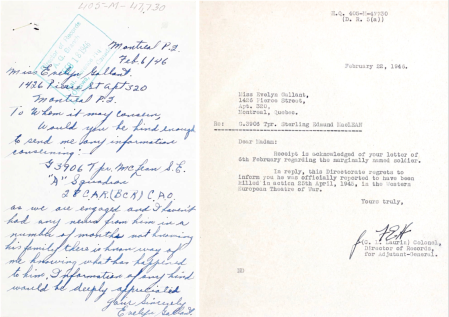

Sterling McLean was engaged to a young woman who lived in an apartment building on Rue Pierce in downtown Montreal, in the shadows of beautiful Mount Royal.

Evelyn Gallant paced the floor, worried about her fiancé because she hadn’t heard from him in a while. Her fiancé’s censured letters from Europe had stopped coming.

Had Sterling been wounded? Was he in hospital? Perhaps he was on his way back to Canada, and they’d be together again …

Or …

Evelyn had no idea what was going on, so she wrote to Army Headquarters in Ottawa. Click on her short letter [lower left] to read what she had to say …

Not long after, the mailman arrived with an envelope from the military. Now Evelyn would know. She tore open the envelope and read the letter. The young woman’s worst fears were realized. She burst into tears. She read the letter again and again.

As the country song goes, war is hell on the homefront too.

VIDEO CLIP

Here’s a short video clip [:25] showing the rugged rocks where the girls died. Click on the arrow to view it.

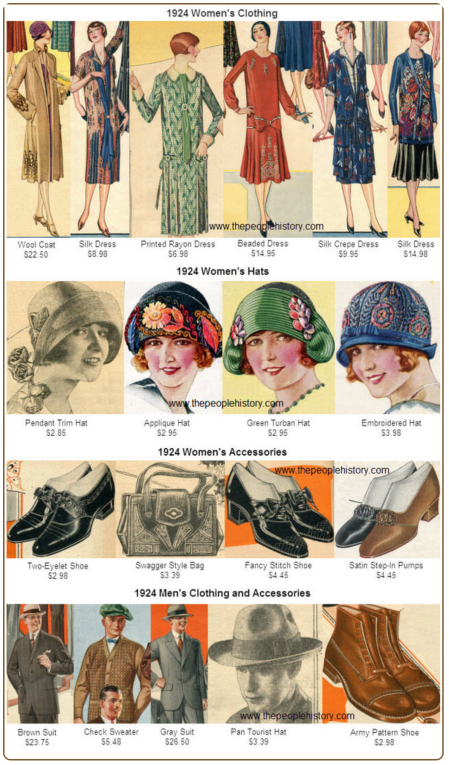

LIFE IN 1924 …

It’s always hard to imagine what life was like before we came into the world. But through popular songs from the “Roaring ’20s” [specifically 1924] — and some key events from that year — we can get a ‘feel’ for what life was like back then.

1924 was the year Prince Edward Island switched driving from the left side to the right … the Royal Canadian Air Force was formed … Prime Minister Mackenzie King made radio history by broadcasting the first federal speech … and in hockey at the first Winter Olympics in Chamonix, France, Canada [represented by the Toronto Granite Club] beat the United States 6-1 in a testy, injury-filled game. Some things never change.

Let’s hear a four-and-a-half-minute compilation of hit songs from 1924 … California, Here I Come [Al Jolson]; It Had To Be You [Isham Jones & His Orchestra]; Somebody Loves Me [Paul Whiteman & His Orchestra] and The Charleston [Arthur Gibbs & His Orchestra].

JOHNSON’S WORK LIVES ON …

Over the years, volunteers have repainted the crosses and removed small trees and shrubbery so the monuments can be seen. In the photo above, taken in 2016, Sugarloaf Parks worker Laura Doucet joins local firefighters in giving the crosses a makeover. [Photographer unknown]

A number of hikers have made the climb to ‘connect’ with the iconic landmark. The author’s estimate of the height of the main rock face is 50-60 feet. [Photo by Author.]

On Thanksgiving Sunday, October 7th, 2018, Campbellton-area women Rose Beek, Monique Boudreau and Gina Menzies attached red flowers to the main cross. It was their way of paying tribute to the Ramsay girls. Boudreau and Menzies are also cancer survivors. They made their way to the crosses with a clear message: mountains, like cancer, can be conquered.

This is not how the Sugarloaf looked in 1924, not even close. There were far fewer trees on the mountain when the Ramsay girls were killed. Click to enlarge to see the rockface in more detail. [Photo by Author in October 2017]

A view of the Sugarloaf in 1927. Because of a fire, there weren’t a lot of trees at the eastern end of the mountain. [Photo courtesy of Edie Power] Click to enlarge.

October 4, 1922: Sugarloaf Mountain on fire. Click to enlarge. [Photo courtesy of historian Irene Doyle.]

AN EVERLASTING MEMORY

Angie Johnson, Alex’s eldest daughter, now in her 70s, lives in the tiny house her father built on Aucoin Street in Campbellton’s west end.

When Angie relaxes on her balcony overlooking the Sugarloaf, she thinks about the two Ramsay girls — and her dad, the painter. Tearing up, Angie offers, “My father was such a kind man.” Motioning to the crosses, she adds, “Look what he did! I am so proud of him.”

Over the years, hundreds of thousands — perhaps millions — have reflected on the two crosses painted by World War One vet Alex Johnson.

Now, that’s a tribute.

THE AUTHOR

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Byron_Christopher

Well done, very good read. Thank you.

LikeLike

Thank you for sharing. Very well done.

LikeLike

Another excellent article.

LikeLike

I would like a story on The Van Horne Bridge. I remember us playing underneath on the catwalk during construction. What a nice revisit.

LikeLike

Wow, What a story. I always wondered what was the truth behind the crosses on the Campbellton Sugarloaf Mountain. Now I know.

No more is it a mystery to me and many others.

Well done.

LikeLike

This is absolutely a wonderful recollection of what’s behind the two crosses!

I’ve lived in Campbellton till 1979 prior to university and honestly had no full understanding of all the facts behind the tragedy.

Thanks for sharing and again showing why Campbellton is a great humanitarian city!

LikeLike

John Ross, born in Campbellton now lives in Miramichi with his cousin Jack Miller, who lives in Fredericton, climbed the path on the eastern side of the mountain in August 1951 … had a picnic there. Beautiful view of Campbellton.

Thank you to the person that posted this article.

LikeLike

Wow. That is truly an in-depth look at the two crosses.

It’s nice to be able to get so much information about them.

Thank you for sharing.

LikeLike

Very well done. Climbed the mountain many times in 1960’s and 70’s.

The last part of east side path was a rock climb. Also remember the path in woods from Brookside to the mountain. Always thought it was spooky in there.

Would like to see more history on my hometown.

LikeLike

I enjoy your articles and images whenever they come up on my Internet horizon. Keep up your fine work!

Best regards from a fellow Campbelltonian now living in the balmy South at sunny Shediac.

Louis Allard (formerly of Queen Street)

LikeLike

I lived in Campbellton for 6 years and did not know this story. My brother and friends climbed Sugarloaf but not I.

LikeLike

We used to climb the Sugarloaf often as kids in the 1960s.

Our family always talked about the Ramsay sisters, telling us to be careful going up there … and to watch for the bears.

Thank you for sharing so many more facts. Interesting read.

LikeLike

Thanks for again writing a great article about our hometown.

My Mom had told me some of the story about the Ramsay girls when I was a child as I wondered what those crosses were all about.

LikeLike

Pingback: My Love Affair with a Mountain ♥ | Byron Christopher

Beautifully written. You tell the story with heartfelt sincerity, a poignant tribute to the girls, their family and their place in the history of Campbellton. Thank you.

LikeLike

Having lived the first 19 years of my life in Campbellton, I’ve always wondered about the significance of the two crosses painted on the face of the Sugarloaf … now I know the facts.

Thank you for sharing. Very well done.

LikeLike

Amazing fact finding. Very impressive.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Frugal Canadian Coupon Mom and commented:

A little history about the Sugarloaf Mountain crosses in New Brunswick!

LikeLike

Have been going up the mountain a few times a week for the past 40 years and although I knew the crosses represented the deaths of the Ramsay sisters it was nice to read the actual story.

Thanks for sharing.

By the way, 22 years ago I took my daughter [who was around 13 years old at the time] up to the crosses. It wasn’t the smartest thing I ever did and was reminded often by the mother. We were able to touch the large cross but couldn’t reach the small one.

LikeLike

Pingback: New Postcards for an Old Home | Byron Christopher

I remember moving to Campbellton in 1971 and being told the story of the crosses.

I read this article and it still breaks my heart. What a tragedy. I’ve always wondered why they would go up the mountain at that time of year and that late in the day.

LikeLike

That thought has plagued me too since I was a little girl.

My Grandparents lived in Campbellton and I spent a lot of time there. I tried to do my own research to find out about the Ramsay sisters.

So sad.

LikeLike

I remember this story and looked it up at the library … a great tragedy for the Ramsay family.

I lived on upper Lansdowne Street and our house faced the mountain so I saw the crosses everyday. As children, we climbed the mountain often; some of the boys used to climb the face.

I was good friends with Linda Johnson and I know her family was proud of their father for painting the crosses.

Thanks for a well-written story.

LikeLike

I was born in Campbellton in 1927. I grew up hearing the account of the Ramsay sisters.

I worked on the CN Railway for 37 years. I knew both Alex and Elmer Johnson. They worked for B&B (bridge and builders). I also knew Syd Ramsay — and knew the police officer that went to the place of the tragedy. My brother and I chummed with his son.

For something to do in those days, we ran up and down the path to the top of Sugarloaf Mountain. We timed it to see who could run up and down the fastest.

It is a great article on the story of the Ramsay sisters … it is good to let the younger generation know a little of the history of Campbellton. Well done.

LikeLike

Great and moving story. Thank you.

LikeLike

This is a wonderful article, Byron. You have a great gift for storytelling and bringing this tragedy to life for today’s generation.

I knew the basic facts of the story but not in such detail – great research! Thank you for taking the time to prepare this thoughtful empathetic account.

I have climbed the mountain a few times too, but never had the nerve to go up the north face – the gradual trek on the east side was plenty challenging enough for me.

I doubt I could climb the Sugarloaf at all these days, even on the path. Last time I was up was about 30 years ago with my friend Charlotte, another teacher. But we were a lot younger. Even then I had to catch my breath many times, and that last 100 feet of sheer rock was a devil to climb. But a beautiful view from the top. That day, as we were sitting there puffing and getting our breath back, we saw a couple of little heads appearing over the north face — two boys no more than 7 or 8 years old who had climbed up the front of the mountain collecting pop and beer cans/bottles — if you can believe it. All of a sudden, our accomplishment withered in comparison.

LikeLike

Very nice for you to share their story.

My mother use to tell me about the two girls that fell but now I have names to put with the story.

Thank you. It was a wonderful and educational read.

LikeLike

Thank you, excellent article … keep them coming … love to read about our Campbellton history.

LikeLike

Great story.

I am told that the Ramsay sisters are distant relatives on my father’s side. I have nothing to substantiate this of course.

LikeLike

Thank you for this amazing article. Each time I read it, I understand your interest.

You are such a wonderful advocate for this area we call home!

LikeLike

Pingback: Giving Thanks | Byron Christopher

Thank you for the in-depth story of the crosses that I used to see every day from my house on George Street in Campbellton. I knew they represented two deaths, but now I know the complete story.

LikeLiked by 1 person

All my life I heard that the two girls had a fight because one sister was sleeping with the other one’s husband. Has anyone else heard this?

LikeLike

I often heard the story of the young women who died on the mountain but never knew the real story now I do its sad may you rest in peace amen thanks for taking the time you but into this story means so much to so many people heart breaking

LikeLike

I love all the articles you write … not having moved far from home, I get to see the Sugarloaf all the time.

I remember as a child our parents telling us this story — not in detail like you wrote it — but basically the same.

We climbed the mountain many times on Sunday afternoons … sometimes 30 of us with our brothers looking out for us.

Thank you once again for a great story. I look forward to your next.

LikeLike

Thanks for sharing.

LikeLike

So special to be able to discover such detailed information and see new pictures, thank you so much!

LikeLike

Thank you so much for writing this article.

I have heard various versions of this story over the years. It is so nice to read this detailed version.

LikeLike

Amazing work putting this together. I appreciate this so much.

Thank you.

LikeLike

I am so happy to see the updates that were added. Opens up more of the mystery for the people that live here in Campbellton. Great job!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank You so much.

LikeLike

Ce n’est pas l’histoire que j’avais entendu. Heureuse d’avoir enfin connu la vérité. On m’avait dit que c’était une mère et sa fille qui cuieillaient des bleuets qui étaient tombées. God bless you girls.

Translation: This is not the story I heard. Happy to finally know the truth. I had been told that it was a mother and her daughter who were looking for blueberries. God bless you girls.

LikeLike

The two ladies were my Mom’s cousins. Mom (Bertha Ryan Lutz) told us that the accident was very suspicious.

LikeLike

This is my great grandfather, Alex Johnson.

LikeLike

Thank you for this great write-up.

It must have been so sad for the family and the whole town as they grieved for this double loss.

LikeLike

I was born in 1941 in Campbellton and left in 1971. I looked up at those crosses many times and was only told that two young girls fell from the mountain. Was never told who they were, or how it happened.

After all these years, I now know.

Beautifully written.

LikeLike

Thanks for sharing, well done. I was born in Campbellton and climbed the mountain many times as a kid picking blueberries and just for the hike.

Great memories.

LikeLike

I was born and lived in Campbellton and climbed the Sugarloaf several times. I really appreciate the history about the girls who lost their lives on the face of the mountain. I looked at those crosses and thought of Dorvil and Lottie many many times!

Thank you and I know the girls are resting in the arms of our Lord!

LikeLike

My name is Charles LeBlanc; I was born in Atholville in 1937. My parents ran the LeBlanc Grocery Store. We moved to Bathurst in 1954.

I knew the reason for the crosses. Really enjoyed the details.

LikeLike

Very interesting to read this story after so many years of knowing about this tragedy.

Our family has a close connection to the history of these two young girls. My grandparents lived in Campbellton and our mother was born there in January 1925 and she was named after the two girls.

My mother was named Dorval Lottie Smith and later married and moved to Winnipeg with her husband Herbert George Gray and raised her 5 children, Glen, Jane, Randy, Margo and Gary who all still live in Winnipeg. Mom passed away in 2007 and dad passed away in 2019 at age 98.

Many of the extended Smith family still live in eastern canada.

I just wanted to add a little information to this story.

Thanks.

LikeLike

Thanks for the update Byron! Hope all is well with you, considering the f*&king virus!

Cheers!

XO

Virus-free. http://www.avast.com

On Fri, Nov 27, 2020 at 6:21 PM Byron Christopher wrote:

> Randy Gray commented: “Very interesting to read this story after so many > years of knowing about this tragedy. Our family has a close connection to > the history of these two young girls. My grandparents lived in Campbellton > and our mother was born there in January 1925 and she wa” >

LikeLike

For nine months we had a nice view of these crosses from our front porch.

In September 1981, we purchased a house at 27 Landsdowne St. Judy and I and 4-year-old Corey were happy to move into this nice 1 1/2 story house, sold to us by a Mr. Smith. We previously lived at 42 Stanley Street, the downstairs portion of Doug Dickie’s house.

Sadly, my Job at CN was cut along with six others in the Technical Services division of the Engineering Department. My family transferred to Saint John in July, 1982.

Some folks may remember my grandmother, Greta MacKenzie, the well-known piano teacher and church organist (33 Andrew Street, right next to the library).

LikeLike